One of songwriter Steve Dorff’s earliest memories involves creating a musical score in his head—while getting pelted by ice during a snowball fight.

For most children, the innate response might be to run or perhaps retaliate with a few well-timed throws of their own. However, Dorff recalls standing still in the center of the group, listening intently as his mind created rhythms and music to accent each swirl of a snowball flying through the air, and the soft punches of snow as they hit against his jacket.

“Everyone else would be cheering it, while I would be musicalizing it. I would underscore in my head everything that was going on around me,” Dorff recalls during a visit to the MusicRow offices. “I assumed everybody did that.”

Dorff was born with synesthesia, a cross-sensory phenomenon that allows some people to hear colors, see sounds, or perhaps see numbers or letters as inherently colored.

“I do remember banging my head against the crib when I was a baby. My mother thought I was having epileptic seizures, but I was trying to create the rhythms I was hearing. I heard orchestras in my mind long before I knew what they actually were. I guess I always knew that music was something I was destined to do,” he says.

Now having been in the music industry for more than four decades, Dorff has more than fulfilled that destiny. Along the way, he has earned 40 BMI Awards and 11 Billboard awards, and has crafted more than 20 Top 10 hits, for an array of pop and country artists including titles for Whitney Houston, Celine Dion, Barbra Streisand, Garth Brooks and George Strait, among others.

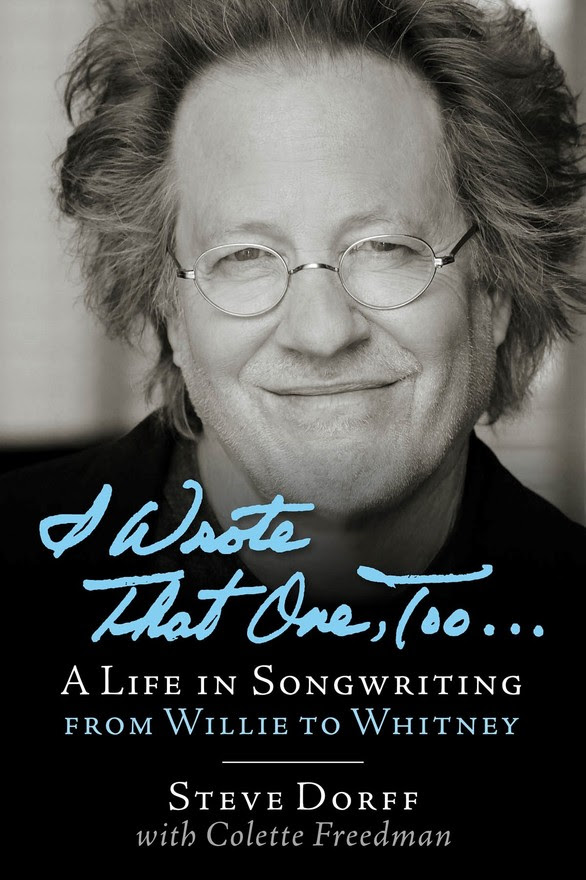

On Nov. 1, 2017, Dorff released his memoir, titled I Wrote That One, Too…A Life In Songwriting From Willie To Whitney (with Colette Freedman, on Backbeat Books), a trove filled with at times humorous, and always honest, stories from a diverse career that has included scoring music for television shows including Reba, Growing Pains, and Murder She Wrote, and movies including Every Which Way But Loose and Pure Country. Most recently, he returned to what he calls his first love: musical theater, scoring for the musical Josephine.

The same month, it was announced that Dorff was named among the elite group of songwriters nominated for induction to the Songwriters Hall of Fame in New York.

How did the idea to write a book come about, and how long did it take you to complete the book?

I was asked to write a book. After I had done one of my [solo performances] Evenings With Steve Dorff. This woman came up and said, ‘I love your stories you should write a book.’ She was a literary agent and she said, ‘I’m going to get you a book deal.’ She gave me her card and a few months later she called me and said, ‘I think I got you a deal, you better start writing.’ That was March 2016. I wrote it very quickly. I had to turn the first draft in on November 15 of 2016.

Were some events and sessions hard to remember?

It was fun because sometimes I’d be thinking about who played on which records. After my first pass, my editor would ask for more details. ‘I want to know what Barbra [Streisand] was wearing. How long did it take? Who played on it?’ So I had to recall those sessions I did 15 or 20 years ago. I remembered pretty much everything, but sometimes I would listen to the record and it reminded me who played on what, because music always does that.

Your son, late songwriter Andrew Dorff, wrote the foreword of the book just before he died in December 2016.

Andrew had called me around the beginning of November, and he said, ‘Who’s going to write that foreword?’ I said, ‘They will probably want Kenny Rogers or someone who has worked with me to do that.’ He said he wanted to write it, and wrote this really cool thing. Our publisher said we didn’t have to worry about the foreword until later on, but when all this happened, I called the publisher and said, ‘This is the forward, this is non-negotiable.’ They were happy to do that and it was beautiful what he wrote.

In the book, you talk about having been able to hear entire scores in your head since you were a young child. Is that still the case?

Yes, that’s why it is so easy for me. When I went into film, writing for movies comes as natural as breathing. I can look at a scene and I can hear it. I don’t have to play or write it. I look at the film without any sound, and I try to create what I’m hearing.

I’m totally piano, though. I can’t play guitar. I sit at my big old Yamaha in my living room. I have a grand piano and there is nothing like the sound of that. The truth is, with most of my ideas, I have 75-85 percent of the song done before I ever sit down at the piano.

Your creative talent has allowed you to compose for musical theatre, score movies and television shows, and write hit songs for radio. What are the differences in scoring and composing for movies, television and musical theatre?

I grew up on theater music more than on rock ‘n’ roll. You are writing as an extension of the dialogue so whatever the characters are, you have to write both musically and lyrically along to how he or she would say it, and just musicalize that, as if you were musicalizing a page or two of dialogue. Musically you are free to do anything—time signatures, changing keys—you have much more creative freedom than writing for radio.

There are tricks and things I’ve learned along the way. For movies and television, if it is a tense scene, there are certain intervals and chords that my ear goes to right away that complement what is happening on the screen. If you dial it down and have it very subliminally, it underscores the action.

What do you recall about writing for Whitney Houston?

What do you recall about writing for Whitney Houston?

I remember getting a phone call from Jermaine Jackson. I had worked with him on a previous album years before, and hadn’t seen him since because the song never came out. He said, ‘I’m looking for a duet song for my album, and I thought of you and wondered if you had something like that.’ Of course I said yes, even though I didn’t. You always say yes. I just stuffed a couple of songs in my pocket and went over to his studio. He jumped into my car and popped the cassette in to play “Take Good Care of My Heart.” By the second chorus he said, ‘That’s it.’ I thought it would be for Dionne [Warwick] or Aretha [Franklin] because they were the best ones on Arista at the time and he said, ‘No, it’s with this new girl.’ I was disappointed, but some of my buddies were playing on the record. They recorded it that night, and I thought it was great. I thought she could really sing. After Jermaine’s album came out, Clive Davis called and told me Jermaine didn’t want it to be a single from his album. Clive was doing a solo album on Whitney and wanted it for her album. I thought, ‘Great, I might sell another 5,000 copies.’ It sold 23 million. That was a big one.

You first came to Nashville in 1971. What are your memories of Nashville at that time?

Being from New York, I wanted to see what Nashville was about. We came up here and stayed in this dumpy hotel down where downtown Nashville is now. Downtown Nashville in the ‘70s didn’t have buildings with more than four floors. I went to BMI and saw producer Bob Montgomery and Billy Sherrill, which was like seeing God. And he actually cut one of my songs with Barbara Fairchild. Back then, the thing that I took away was it’s a little music community that has it’s power brokers and has its setup and you gotta get through certain barriers to get to the guys who make the decisions, much like it is today. I didn’t understand how the business worked back then as well as I do now. Coming from New York, where there were hundreds of “camps,” I understood if I wanted Andy Williams, I went to Columbia and tried to find out the powers that be there. In Nashville it’s so close-knit, it’s like one camp. And it’s still that way, just the names have changed.

You scored the soundtrack to George Strait’s 1992 movie Pure Country. What was different in how you approached that movie?

I met with Chris Cain who [directed] Young Guns and Where the River Runs Black. He knew how he wanted to shoot this movie. They sent me the script and I knew we would have to find songs and pre-record a lot. I had never really done that. I had done a few with the [Clint Eastwood] movies but not on the scale of this, where [lead character Dusty Chandler] is playing in front of 25,000 people.

Tony Brown was very involved in the song selection. I came in with two songs, “Heartland” and “I Cross My Heart.” “I Cross My Heart” was a song that Bette Midler had recorded eight years before, which kept us from getting an Academy Award nomination for it. She had tried singing it several times, but in the end, she didn’t feel like it was the right fit for her at the time.

When I played that song for Tony and George, he basically said, ‘I’m not doing a Lee Greenwood album,’ and George really didn’t like “Heartland,” but it was right for the film. A great deal of my success has been the bridge that film and TV and yet knowing how to write songs that work in this format. The power of movies and television really elevated it.

Several of your hits were in your catalog for years before they were released. You wrote “Baby Let’s Lay Down and Dance” in 2001, and it became the first single off Garth Brooks’ 2016 album, Gunslinger.

I keep digging back and pitching songs, and trying to give facelifts to demos of songs I really believe in. I do that with Andrew’s catalog too. Andrew and I used to argue about how he would write 250 songs a year and if I write 15 songs a year, that’s a big year for me. I’ll go months sometimes without writing a song, so to think some of these great writers are writing five songs per week is mind-boggling.

So we playfully argued, ‘How do you have that many ideas?’ But he did. He was brilliant as an idea guy, but he tends to always go with what he wrote yesterday and he would forget some of the great songs he wrote two or three years ago. Now I’m given that charge since he is not here to go back and mine that catalog and try to find homes for some of those songs.

About the Author

Jessica Nicholson serves as the Managing Editor for MusicRow magazine. Her previous music journalism experience includes work with Country Weekly magazine and Contemporary Christian Music (CCM) magazine. She holds a BBA degree in Music Business and Marketing from Belmont University. She welcomes your feedback at jnicholson@musicrow.com.View Author Profile