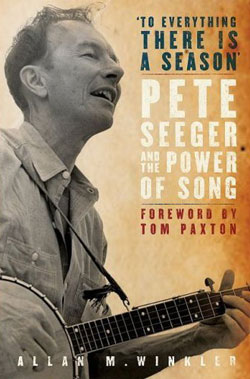

In the new Pete Seeger biography, To Everything There is a Season: Pete Seeger and the Power of Song by Allan M. Winkler (Oxford University Press, 2009), the author notes that throughout his life, Seeger “didn’t smoke, drink or chase women; instead he chased causes.”

In the new Pete Seeger biography, To Everything There is a Season: Pete Seeger and the Power of Song by Allan M. Winkler (Oxford University Press, 2009), the author notes that throughout his life, Seeger “didn’t smoke, drink or chase women; instead he chased causes.”

Pete Seeger’s life was “singing truth to power” and author Winkler notes that “The labor movement of the 1930s, the peace movement on the eve of World War II, the civil rights and antiwar movements of the 1960s, and the green crusade for clean water all bear the mark of Seeger’s melodies and echo the rhythms of a century of change.”

Seeger came from a privileged background and attended Harvard before dropping out because he “wanted to use music—his kind of music—to make the world a better place. Above all he wanted to use music to help the growing labor movement achieve its aims of respect for the dignity of working men and women and of play levels that would allow them to survive and prosper. He dreamed of being in the forefront of workers singing songs that created a sense of common identity.”

In 1940 Seeger met Woody Guthrie, the major influence on his life, and the two formed the Almanac Singers. A radical from his earliest days, Seeger’s politics rankled—and still rankle—many. According to Winkler, Seeger “was, and is, a communist in the pure, idealistic sense of wanting equality for all—no rich, no poor—just everyone sharing together.”

His communistic sympathies got him into trouble during the Communist hunts of Joseph McCarthy in the early 1950s. By this time, Seeger had formed “People’s Songs,” an “informal association to encourage the creation and spread of radical protest songs.” That organization, formed in 1946, held a national convention in Chicago but fell into bankruptcy and closed its doors in 1950. However, the core group of people who worked with “People’s Songs” established the folk music magazine, Sing Out!

Seeger was a member of the group The Weavers, along with Fred Hellerman, Ronnie Gilbert and Lee Hayes, whose hits included “Good Night, Irene,” “On Top of Old Smoky,” “Kisses Sweeter Than Wine” and “So Long, It’s Been Good To Know You.” The group was incredibly successful, selling over four million records in two years before the McCarthy hearings came knocking.

The question was asked “Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?” and Seeger replied, “I am not going to answer any questions to my associations, my philosophical or religious beliefs or my political beliefs, or how I voted in any election or any of these private affairs. I think these are very improper questions for any American to be asked, especially under such compulsion as this.”

Seeger had Communist connections and Winkler pointed out that he sympathized openly with Communism’s egalitarian goals, he read the Daily Worker, and he had even been a formal member of the Party for a time.”

The summer of 1951 was a difficult one for Seeger and the Weavers bookings dwindled to almost nothing before they held a final concert in December, 1952 in Town Hall in New York but in 1955 the Weavers reunited although Seeger left the group in 1957 to sing on his own.

Meanwhile, Seeger was indicted for “contempt of Congress” in March 1957 on ten counts. At his trial in 1961 he was sentenced to a year in prison but the conviction was overturned on a technicality. Seeger took it all in stride, saying “Being indicted just gave me a lot of free publicity.” However, Seeger was blacklisted and could not appear on the TV networks for a number of years. Seeger became a one man band, leading audiences in songs. Creativity as synthesis is part of the folk tradition, taking songs, lyrics, melodies and ideas from the past or just “floating around” and forming a new song. In that manner, Seeger is responsible for songs like “If I Had a Hammer,” “We Shall Overcome,” “Turn, Turn Turn” and “Where Have All the Flowers Gone.” It is an impressive legacy.

Emerson wrote “If a man plant himself on his conviction and then abide, the whole huge world will come round to him” and that may hold true for Pete Seeger, still alive and going strong in his 90s. In October, 1994 he was awarded the National Medal of Arts and in December of that year was honored at the Kennedy Center. In 1997 he won a Grammy and in 1998 the Library of Congress named Seeger one of “America’s Living Legends.” In 2006, Bruce Springsteen did a tribute album to him, The Seeger Sessions.

Seeger has said “I don’t want people to forget their struggles” and continues to be committed to music that furthers causes. For a number of years he has been involved in the environmental movement, helping clean up the Hudson River. He has remained a lightning rod for criticism while, at the same time, has become a conscience for the music business. Author Winkler notes that Seeger’s “success in getting others to sing—something he had sought all his life—was a testament to the power of song.” It’s also testament to the power of an individual.

About the Author

Don Cusic is Professor of Music Business at Belmont University. He has authored 18 books, including his most recent “Discovering Country Music.”View Author Profile